“Only when you are truly local can you even hope to be global”, Damon Galgut said in the recent edition of The Hindu Lit for Life festival. And how perfect an example of this is Sadanam Balakrishnan. An artist secure in his grasp of the ethos of his art form, indeed as one who creates that ethos now, his work exemplifies how global an artistic effort can be when it is unapologetically, unflinchingly rooted in the tradition, in the local.

“Kathakali is called a classical dance for of India,” he started after apologizing for his “inability to talk much English”. And then with a casual sweeping gesture he said: “I don’t know what that means. But this I can say – that Kathakali is a highly stylized, traditional dance drama form of Kerala.’ When other dance forms and music forms are clamouring for a status of the “classical”, here was a prominent performer of a dance form with a “classical status” dismissing it. What does it mean anyway to call our music and dance forms classical?

“Kathakali is a very demanding art form and our training takes places over 10-12 years for more than 12 hours a day. So there is no space for schooling and higher education.” He said, perhaps again to indicate what one might expect from him. And yet, it requires a sophisticated and secure mind that can dismiss a State recognized category. Many of our other artists with college degrees may not have this kind of self awareness. And is not self awareness precisely the point of education? And then what sense can we make of the compulsory education drive of the State? Would it not displace, render illegitimate such profoundly rooted and well rounded “education systems” of which Sadanam Balakrishnan and his ilk are products?

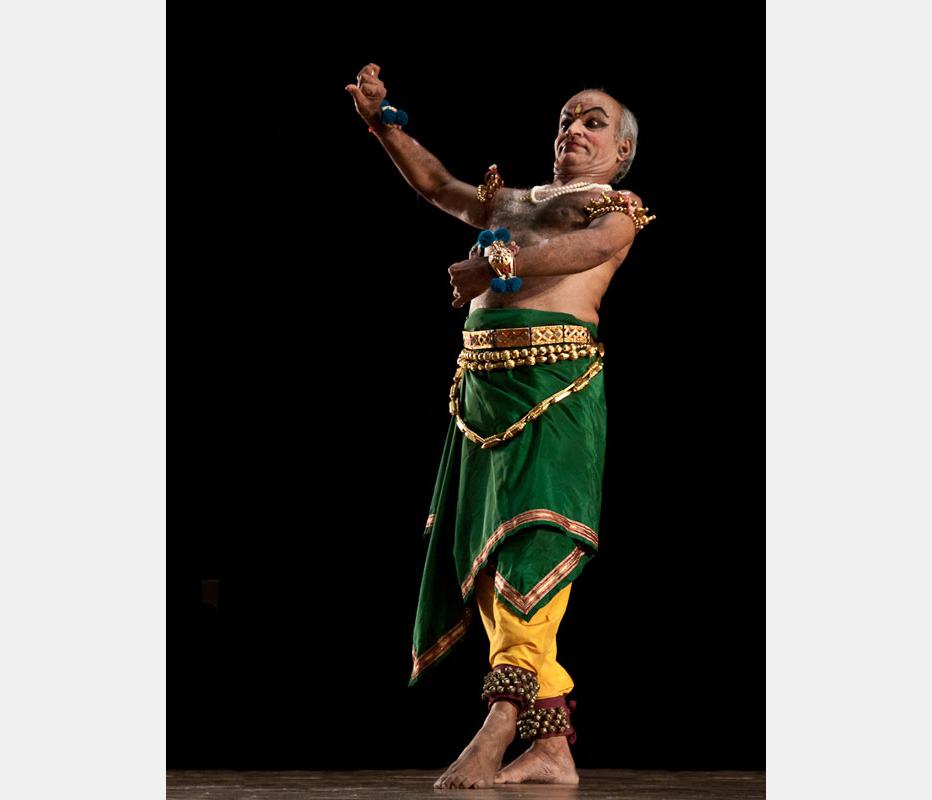

Such questions in the mind jostled with admiration for his sheer artistry as he took us through basics of Kathakali. Sadanam Balakrishnan was one of the artists featured in the 2 day “Liberation Through the Arts” seminar organized by the Vishnumohan Foundation in the serene premises of the Theosophical Society. Others featured were Gopika Varma, M.V.N. Murthy, Shama bhate, Yashwant Sharan and Krithika Subramaniam.

How does one address such an abstract theme? Balakrishnan began with a simple principle – “We live in service to the art. When we worship our art, there is no need to worship anything else.”

He demonstrated control of facial muscles to depict the various bhava-s, and went on to “mukharaga” – change in the colour of the face as there is a change of bhava. “We can’t really see the colour of the face since we have heavy make up on the face, but you can feel the change…” Kathakali places equal value on all the four abhinaya aspects as mentioned in the Natyasastra. Angika, vacika, aharya and saativika. Saatvika abhinaya requires control of the mind, he said, and students are trained in this too; this, we know, is the first step towards “liberation”.

Kathakali is out and out natyadharmi – stylized; there is no place for lokadharmi or realism. Everything – the make up, the movements, the costume, and indeed the stories told are grander than life. He demonstrated a lady playing with a ball with magnificent restraint and grace – no woman could have possibly done a better job. “Traditionally, all roles – male and female – are played by men; nowadays we have many girls and women learning the art, so there may be no need for men to play the roles of women. But”, he continued with a smile and eyebrows raised, “women actors actually prefer to play the part of men and this is to be encouraged because that is truly in the spirit of natyadharmi. And men playing women should also continue.”

He wound up his presentation with a riveting performance of a piece from Mali Madhavan Nair’s Karnasapatham depicting Karna’s anguish on the eve of the Mahabharata war. Karna is tormented by doubts of his birth. “Mother Radha and father Adhirathan – I don’t think they are my parents. Tomorrow the war begins and I may die – am I to die without even knowing who my parents are, without meeting them even once?” As stylized as the performance was, as “unreal” as it was, the communication of the universal condition of man came through poignantly.

“A successful performance does not draw applause,” he said gently: “the audience, the actors all become one in the rasa experience. Not applause but tears – that is proper.”

Arts can be liberating – momentarily – as Pt. Nikhil Banerjee said in an interview: “good literature, good poetry, good picture, good music lifts you up and you forget your whole body and surroundings. That is the purpose of art. That it will take us up towards God, you could say, or towards Space, beyond all these things”.

And what is this primal, gnawing need for us to be free of ourselves? That is the mysterious question.

(unpublished)